1. Vertigo (Hitchcock, 1958)

2. Der Müde Tod (Fritz Lang, 1921)

3. Salo o le 120 giornate di Sodoma (Pasolini, 1975)

4. Zerkalo (Tarkovskij, 1975)

5. Sunrise (Murnau, 1928)

6. Sherlock Jr. (Keaton, 1924)

7. Blue Velvet (David Lynch, 1986)

8. Notorious (Hitchcock, 1946)

9. Smultronstället (Bergman, 1958)

10. Offret (Tarkovskij, 1985)

11. La Double vie de Veronique (Kieslowski, 1991)

12. Psycho (Hitchcock, 1960)

13. Vampyr (Dreyer, 1932)

14. Rear Window (Hitchcock, 1954)

15. Videodrome (Cronenberg, 1983)

16. Medea (Pasolini, 1969)

17. Le testament d’Orphée (Cocteau, 1960)

18. The Grand Illusion (Renoir, 1937)

19. Ma nuit chez Maud (Rohmer, 1969)

20. Letter from an unknown woman (Max Ophuls, 1945)

21. I vitelloni (Fellini, 1953)

22. Hiroshima mon amour (Resnais, 1959)

23. The Conformist (Bertolucci, 1970)

24. Teorema (Pasolini, 1968)

25. La Pianiste (Haneke, 2001)

26. Tokyo Story (Ozu, 1953)

27. Sans Soleil (Marker, 1983)

28. Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens (Murnau, 1922)

29. Mouchette (Bresson, 1967)

30. Death in Venice (Visconti, 1971)

31. Paris, Texas (Wenders, 1984)

32. Cache (Haneke, 2005)

33. The Dead (Huston, 1987)

34. Mr. Arkadin (Welles, 1955)

35. The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (Bunuel, 1972)

36. The Conversation (Coppola, 1974)

37. Persona (Bergman, 1966)

38. Days of Heaven (Malick, 1978)

39. Citizen Kane (Welles, 1941)

40. Amarcord (Fellini, 1973)

41. Double Indemnity (Wilder, 1944)

42. The Spirit of the Beehive (Erice, 1973)

43. Import/Export (Seidl, 2007)

44. The Fire Within (Malle, 1963)

45. Seven Samurai (Kurosawa, 1954)

46. Taxi Driver (Scorsese, 1976)

47. La passion de Jean d’Arc (Dreyer, 1928)

48. Ordet (Dreyer, 1956)

49. Le sang d’un poete (Cocteau, 1931)

50. In a Lonely Place (Nicholas Ray, 1956)

51. Nightmare Alley (Edmund Goulding, 1947)

52. Wages of Fear (Clouzot, 1953)

53. Det Sjunde Inseglet (Bergman, 1957)

54. The Birds (Hitchcock, 1963)

55. Kwaidan (Kobayashi, 1964)

56. Le Cercle Rouge (Melville, 1970)

57. Fat City (Huston, 1973)

58. Love and Death (Woody Allen, 1975)

59. Stalker (Tarkovskij, 1979)

60. Viridiana (Bunuel, 1961)

61. Sporloos (Sluizer, 1988)

62. Zodiac (Fincher, 2007)

63. The Cranes are Flying (Kalatozov, 1957)

64. Drunken Angel (Kurosawa, 1949)

65. Häxan (Christensen, 1922)

66. The Lady Vanishes (Hitchcock, 1938)

67. McCabe and Mrs. Miller (Altman, 1971)

68. The Treasure of Sierra Madre (Huston, 1948)

69. Limelight (Chaplin, 1952)

70. Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf (Nichols, 1967)

71. Le Locataire (Roman Polanski, 1978)

72 Aguirre (Werner Herzog, 1972)

73. Antichrist (Von Trier, 2009)

74. Au hasard Balthazar (Bresson, 1966)

75. Man Bites Dog (Belvaux, Bonzel 1992)

76. The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (Wiene, 1920)

77. Distant Voices, Still Lives (Terence Davies, 1988)

78. The Flowers of St. Francis (Rosselini, 1950)

79. Autumn Sonata (Bergman, 1978)

80. Annie Hall (Woody Allen, 1976)

81. Invocation of My Demon Brother (Kenneth Anger, 1969)

82. Last Year at Marienbad (Resnais,1961)

83. The 400 Tricks of the Devil (Melies, 1906)

84. Nanook of the North (Flanerty, 1922)

85. Sisters (De Palma, 1973)

86. The Long Goodbye (Altman, 1973)

87. The War Game (Watkins, 1965)

88. The Killing (Kubrick, 1956)

89. Anatomy of a Murder (Preminger, 1959)

90. The Killing of a Chinese Bookie (John Cassavettes, 1976)

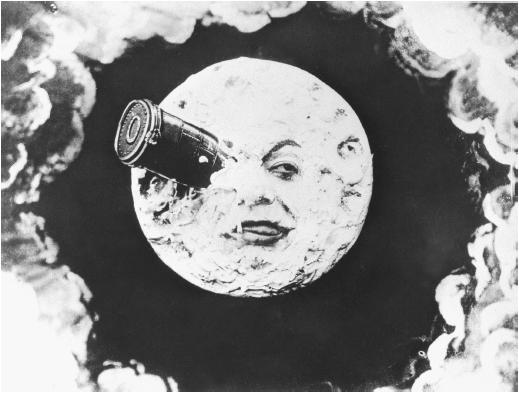

91. A Trip to the Moon (Melies, 1902)

92. Meshes of the Afternoon (Maya Deren, 1943)

93. Nagareru (Naruse, 1956)

94. Barton Fink (Coen, 1995)

95. Pickup on South Street (Fuller, 1953)

96. The Crowd (King Vidor, 1928)

97. The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (Fritz Lang, 1933)

98. Foreign Correspondent (Hitchcock, 1940)

99. Nights of Cabiria (Fellini, 1957)

100. Hour of the Wolf (Bergman, 1968)